Social Service Workforce

Understanding how frontline workers can protect children and vulnerable groups

Introduction

Think about a time when you received a service. You may have gone to a health clinic to get your child vaccinated or registered your marriage at a government office. To access these services, you most likely interacted with another person – a healthcare worker, a social worker, a social protection administrator, etc.

These people are known as front line workers. They are professionals who interface with people daily to provide goods and services. In a world where attention is limited and information is abundant, their interactions with individuals, families and communities have the power to shape attitudes, and ultimately behaviours. Frontline workers come from many professional backgrounds and are central players in Social and Behaviour Change.

We will focus on one important group of frontline workers: social workers. They are often the first line of response for children in harm's way. They work closely with children and families to identify and manage risks that children may be exposed to within and outside of the home, especially those related to violence, abuse, exploitation, neglect, discrimination and poverty. They promote children’s physical and psychological well-being by providing and connecting them to critical social services such as healthcare, education and social protection. Social workers also challenge harmful norms that may violate a child’s rights.

These workers have the opportunity to promote positive roles, norms and practices in relation to gender, disability, ethnicity and other areas vulnerable to discrimination. They have the power to secure healthier relationships, social inclusion and positive outcomes for community members.

Evidence suggests that interventions that do not engage social workers are more likely to encounter resistance, disengagement, apathy or disinvestment at the community level. The capacity of the social service workforce to mobilize communities and proactively communicate with families and groups is critical to achieving positive and sustainable change at the individual, family and community level.

The purpose of this tool is to provide guidance on designing and evaluating capacity-building programmes for social workers. For further support, we have included links to case studies and additional resources.

Benefits and social/behavioural objectives

- Building trust. Social workers hold a uniquely trusted position within communities. Beyond their ability to connect with community members through shared language, social workers are often related to or have a strong connection with the communities they serve. They use their skills and knowledge of the community to build rapport and engage opinion leaders (religious leaders, community leaders, teachers, traditional healers, nomadic leaders) who play a crucial role in engaging unmotivated and/or hard to reach individuals.

- Change behaviour. Social workers are trained to consider problems and solutions through a multi-level framework and a contextual lens. They must account for the challenges, social norms, communication barriers and other protective and risk factors relevant to the communities they serve. Their enhanced knowledge and ability to work collaboratively with communities, individuals and families help in the design of solutions that are more likely to change behaviour.

- Collecting rapid insights. In addition to working on the frontline, social workers often function as a community’s eyes and ears. They act as a bridge between the system, services and local needs, by providing critical feedback, advocacy and insight from the community to inform service and policy design. Social workers are incredibly valuable for crafting SBC interventions and additional research, and helping communities hold key stakeholders accountable to change.

- Ensuring programme sustainability. Social workers are trained in community engagement, and act as an advocate/promoter for the communities they serve. They contribute significantly to the achievement of UNICEF’s programme goals by empowering communities through a strength-based approach to community needs and directions. Additionally, they play a key supervisory role, providing development and mentoring support to advance and sustain the core competencies required to build an effective workforce. Developing a localized or regional community of practice to promote collective or shared peer learning can improve capacity-building for training and supervision.

Implementation steps

As Figure 1 illustrates, there are knowledge and skill sets that are useful for a variety of different social service occupations (at levels 2 and 3). There are also competencies that are fundamental to a range of social service occupations (at level 1). Level 1 competencies include:

- Knowledge of social-ecological models of human development, including the bio-psycho-social model of disability

- Human rights and people-centred approaches

- Interpersonal communication

- An understanding of helping and empowerment processes

- The ability to mobilize groups, families and communities towards SBC in a variety of settings without discrimination or judgement

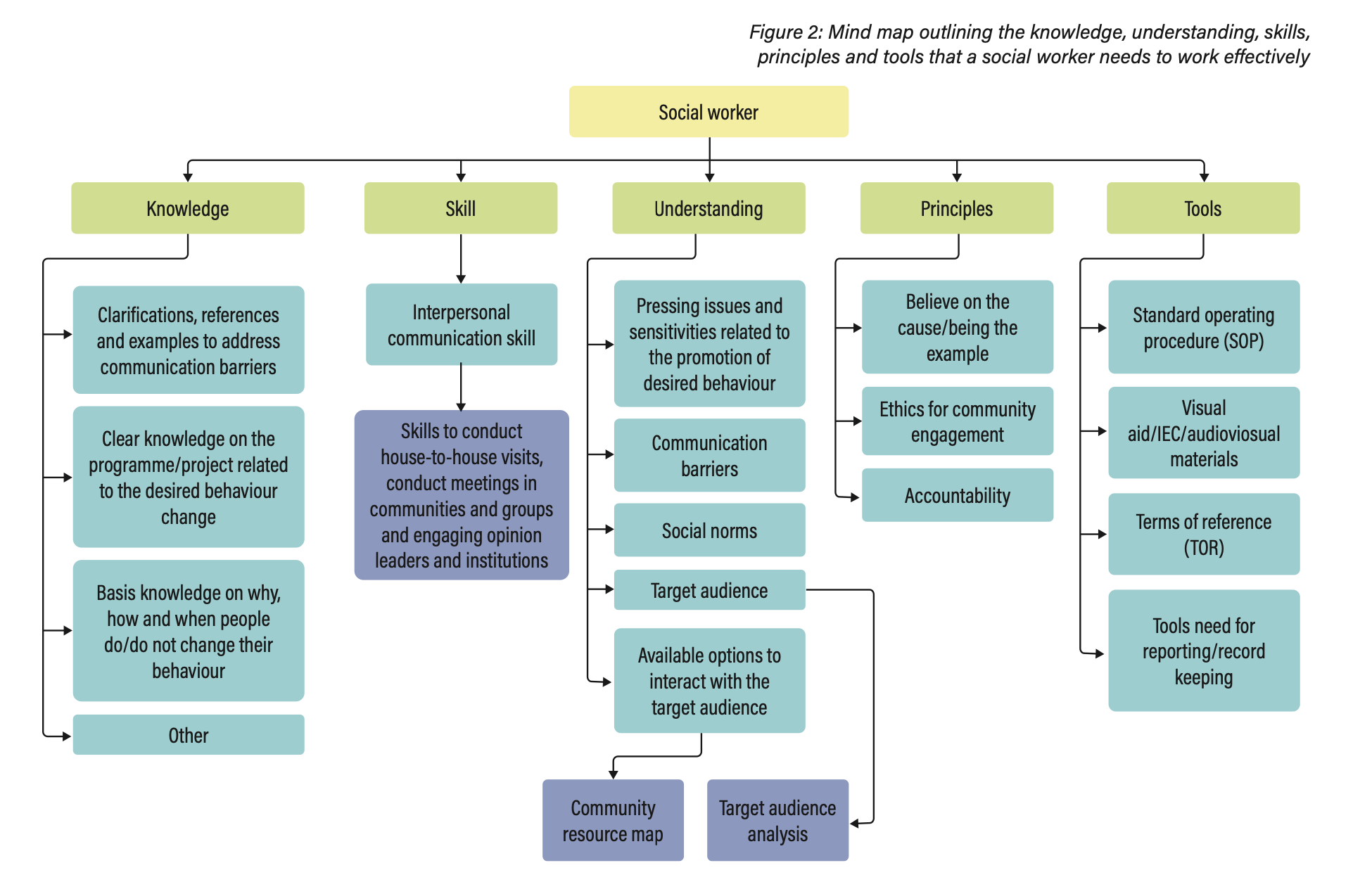

In order to develop capacity-building training for the social service workforce, it is important to understand their perspective and the environment they operate in. A social worker should be equipped with five key things: (i) knowledge, (ii) understanding, (iii) skill, (iv) principles, and (v) tools. As with any workforce, proper practice and on-the-job training is recommended to build competencies and ensure high-quality service. Therefore, it is vital to incorporate ample scope for practice and learning through role-playing, self-reflection and analysis of case studies during training sessions.

Upon recruitment, formal training is required to equip social workers with the necessary understanding, knowledge, skills, principles and tools to succeed. Periodic on-the-job refresher trainings can complement academic achievements and supportive supervision, to further strengthen their skills, understanding and use of tools. The duration of formal training will depend on the qualification of the workforce, country context, skill level of trainers and time and budget constraints.

Above all, the number and variety of role-playing activities and case studies should be maximized, so that participants can learn by practising their techniques in real life. Below is a table that provides example topics and methodologies for each of the five key modules.

Table 1: Example topics and methodologies for each of the five key modules

Module | Programme-specific content | Generic content | Example methodologies |

Principles |

|

|

|

Understanding |

|

|

|

Knowledge |

|

|

|

Skills |

|

|

|

Tools |

|

|

|

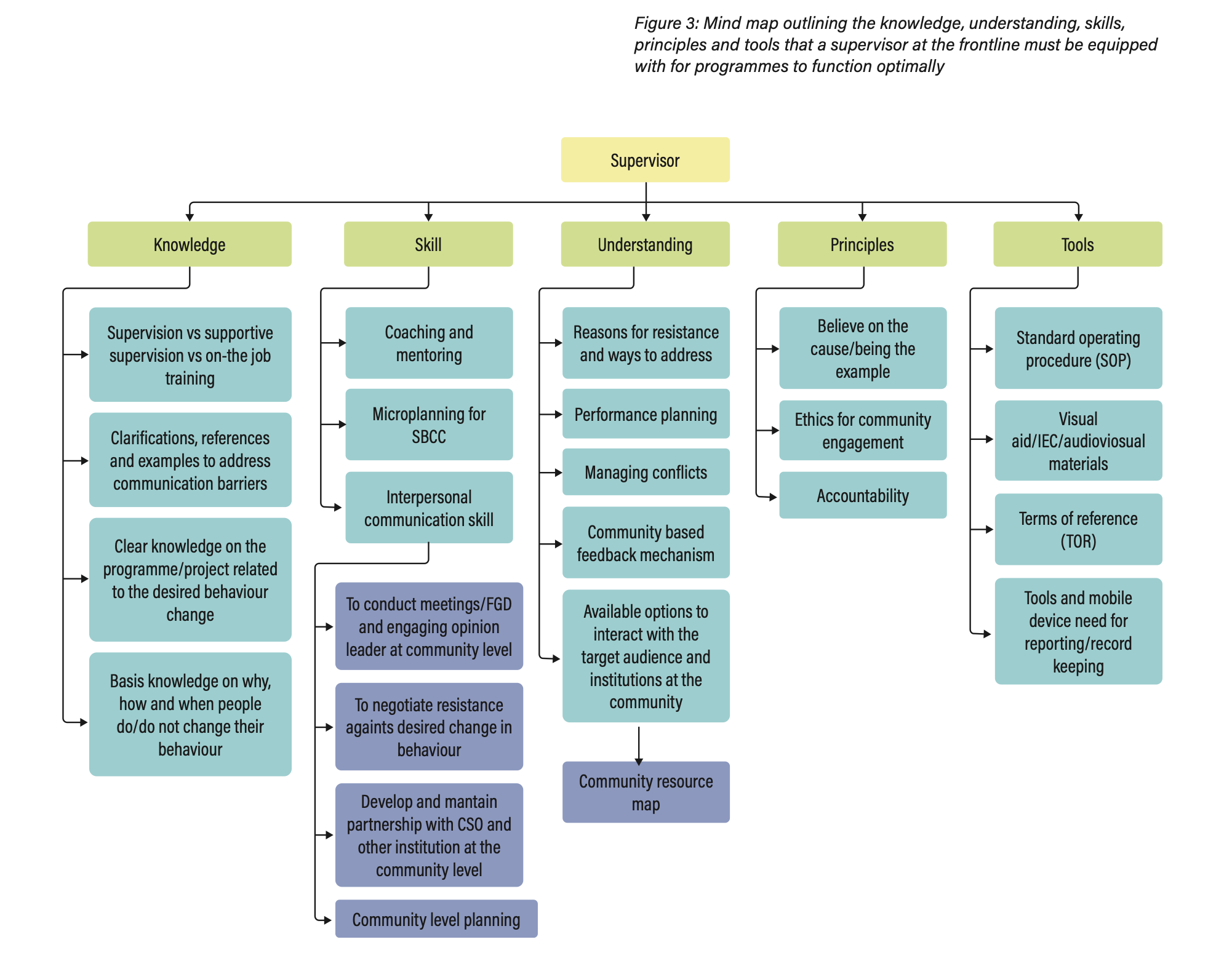

While training social workers is essential to facilitate SBC at the community level, supervisors should also be equipped with the necessary skills and tools to empower them to fulfil their roles. The mind map below outlines the knowledge, understanding, skills, principles and tools that a supervisor at the frontline must be equipped with for programmes to function optimally.

To better grasp their roles and responsibilities, supervisors should ideally have training in social work or another social service profession. Such training can be leveraged to better understand the context as well as the knowledge and skill level of their staff, enabling them to be a model and resource for them. While supervisory training modules should resemble the contents of the table above, formal training should also include core standards and address the following topics:

- The purpose of supportive supervision and on-the-job training

- Improving programme/project/service awareness through SBC communication

- Communication skills for supportive and flexible supervision

- Coaching and mentoring by building a reflective practice

- Enhancing motivation via nudges and boosts

- Leading SBC quality improvement

- Workplace harmony and stress management

- Supervising frontline workers

- Self-assessment for supportive supervision

Measurement

When measuring the effectiveness of training or capacity-building, there are three major questions to consider:

- Did people complete the training? Low completion rates signal the need to make changes to the training, enhance understanding of trainee expectations and improve engagement. They also provide an understanding of how long it takes to complete the training, allowing designers to assess whether it aligns with their goals. This assessment may reveal unanticipated areas of difficulty. Be sure to measure the:

- % of people who complete the training

- Time needed to complete the training

- Areas of training drop-off

- How satisfied are you with the training on a scale of 1 (not satisfied) to 5 (extremely satisfied)

- Did you learn anything new?

- Was the objective of the training met?

- How can this training be improved?

- What did you like/dislike about the training?

- Are there differences in learning and confidence before and after the training? Test the knowledge of participants prior to training to establish a baseline, then test again after training. Higher scores suggest that the training is effective.

- Are people satisfied with the training? Qualitative feedback is always valuable. Feedback can be used to improve training delivery to better serve future trainees. Qualitative feedback can be collected regularly throughout the training, and at the conclusion. Feedback surveys may include the following questions:

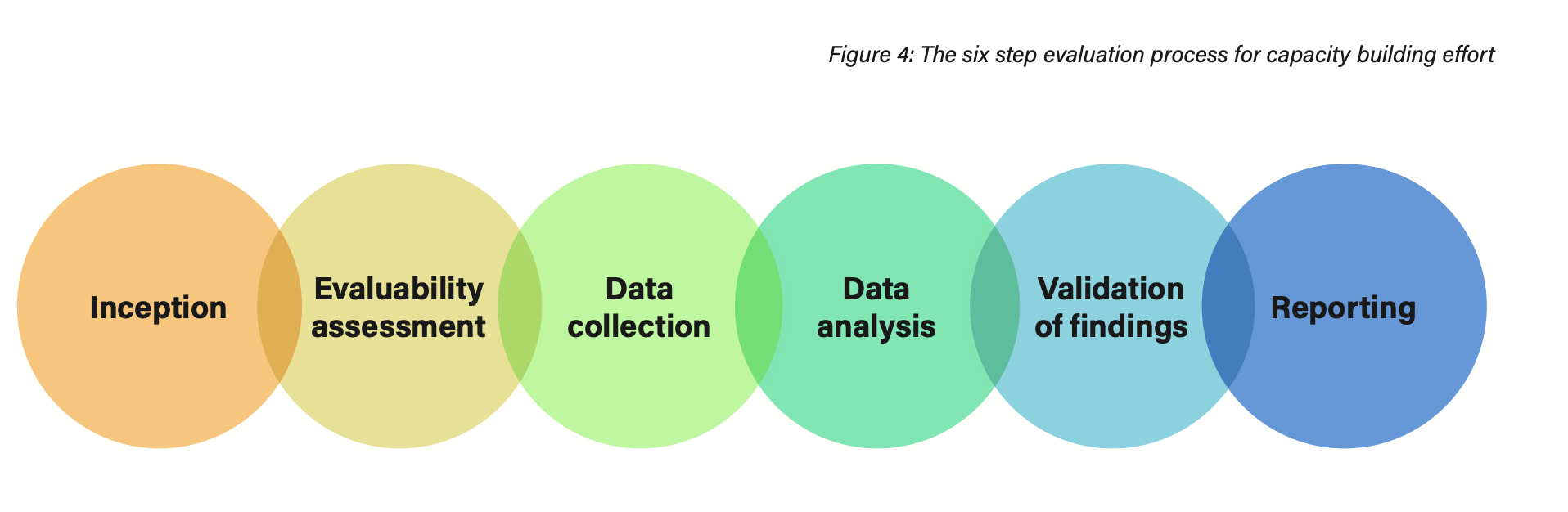

To assess training and capacity-building interventions as a whole, a more methodical and holistic approach is required. Your approach depends on various factors, such as time, budget, data and technical expertise. Using a six step evaluation process (including other capacity-building efforts such as on-the-job training, supportive supervision, etc.) is highly recommended. These six steps are outlined in Figure 3 and described below.

- Inception: The entire evaluation process is conceptualized at this stage, starting with an objective for the evaluation. When designing the methodology for evaluation the following indicators/areas should be considered for data collection:

- A training programme with a clear goal

- A comprehensive training database

- A comprehensive trainee database

- A Theory of Change aligned with training and other capacity-building efforts

- Programmatic and operational relevance

- Effectiveness and efficiency

- Training curriculum and content aligned with accepted technical standards and academic texts

- Sustainability of lessons and skills learned

- Incorporation of cross-cutting issues and evidence-based practice

- Provision of practice and application in real life

- Evaluability assessment: When designing tools for data collection, different indicators will be considered. It is important that the amount of collected data be statistically representative of the real-life scenario. Whenever possible, incorporate standardized measurements in order to be able to generalize outcomes more broadly.

- Data collection: Your data collection methods will depend on time, budget, logistics and scale. Combining methods is highly recommended, to increase the likelihood of all relevant perspectives being collected. Common methods include:

- Document review

- Interview

- Focus group discussion

- Questionnaire (physical or digital)

- Data analysis: A well-designed evaluation should collect qualitative and quantitative data for analysis. Software such as Microsoft Power BI, Microsoft Excel and SPSS is popular for quantitative data analysis. Excel is a very powerful tool for data cleaning, and a prerequisite for quantitative data analysis. Common theoretical approaches to evaluating qualitative data include:

- Validation of findings: After the data has been analysed and interpreted, the findings are often summarized in a document or presentation format to share the findings widely and arrive at a consensus. It is highly recommended to host a workshop or webinar to discuss and validate findings shared beforehand or during a Community of Practice meeting. This step is essential to triangulate collected data.

- Reporting: After validation, a narrative report with visual presentation of data is prepared. This report can be shared online or through printed publications, briefs or presentations. The report should be shared in every possible way.

Partnerships

Partnerships can contribute to the success of many aspects of capacity-building for social workers. The partnerships you pursue will depend on the context and need. Partnerships can be formed with organizations such as specialized government agencies, INGOs/NGOs with capacity and infrastructure to support training, specialized training organizations, government agencies, UN agencies (including he UNHCR, the IOM), research agencies and academic institutions.

Case studies and examples

- THE NETHERLANDS: Frontline workers can play an important role in helping women (and their partners) to be aware of IPV, to identify abusive relationships and to make them aware of the consequences of abuse for the child.

- UZBEKISTAN: USWEEP has been designed to assess the current state of the social service workforce (SSW) and strengthen social work education and practice through sustainable approaches.

- BANGLADESH: Intensive interpersonal communication of frontline workers, when combined with a nationwide mass media campaign and community mobilization, helped increase complementary feeding practices.

- BANGLADESH: Secure Digital (SD) cards are being used by frontline workers. The SD cards store content such as job aids/tools/patient materials, for easy access via mobile phone during interpersonal counselling sessions. They have greatly reduced the physical demands placed on frontline workers who traditionally have had to hand-carry heavy items such as flipcharts and projectors.

- NIGERIA: An independent evaluation identifies key shortcomings in training efforts

- EUROPE AND CENTRAL ASIA: Building Competencies for the Social Service Workforce on Community Engagement and Interpersonal Communication in Europe and Central Asia Region

Key resources

- Interpersonal communication for immunization: Reference card

- Risk Communication: A handbook for communicating environmental, safety and health risks, Fifth Edition, Regina E Lundgreen and Andrea H. McMakin

- Materials from the University of Michigan’s online course “Community Engagement: Collaborating for Change”

- Materials from the National University of Singapore’s online course “Understanding and communicating risk”

- People in Need’s Behaviour Change Toolkit for international Development practitioners (2017)

- Supportive Supervision: A manual for supervisors of frontline workers in immunization, 2019, UNICEF-NYHQ

- Trainers’ facilitation guide: Interpersonal communication for immunization package, 2019, UNICEF-NYHQ

- Practical guidance for risk communication and community engagement (RCCE) for refugees, internally displaced persons (IDPs), migrants and host communities particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 pandemic, UNICEF-IOM-UNHCR-WHO-IFRC, UNODC-John Hopkins, Center for Communication Programs

- Pan American Health Organization’s Zika Virus Infection: Step by step guide on risk communications and community engagement (2016)

- Expanding the Field of Social Work in Europe and Central Asia