Behavioural Science to adapt to the planetary crisis

How Insights into Human Behaviour Can Enable Societies to Adjust to the Planetary Crisis

Introduction

The negative effects of climate change will, to varying degrees, impact the lives of every person on earth today, especially children. Although we may still be able to mitigate the worst effects of climate change through a transformative shift in how we live, many climate-related impacts are already locked in and cannot be prevented; the unavoidable result of past human actions. In the face of these inevitable effects and the high likelihood of worse impacts from future harmful actions, it is vital that we adapt to the new realities of life on a warming and degrading planet and build individual and societal resilience to the negative consequences of the planetary crisis.

However, getting people to adapt their lives to protect themselves against the effects of the climate crisis can be challenging. The long-term consequences of climate change can be perceived as too abstract, complex, and spatially and temporally distant for people to comprehend the urgent need to adapt. Convincing the public to start adapting to climate change now requires an understanding of how people perceive climate change and its potential impacts as well as how they make decisions around it.

Behavioural science research provides insights into the psychological mechanisms that are preventing communities from building resilience and taking sufficient steps to prepare for and adapt to the changes brought on by the planetary crisis. Understanding how people think about the risks of climate change for their own communities, families and themselves can help to identify the best strategies to encourage adaptative action and resilient behaviours.

Adaptation and Resilience: related but distinct concepts

Adaptation and Resilience: related but distinct concepts

“Adaptation” and “Resilience” are often used interchangeably in discussions on climate and disasters. However, while they are complementary concepts, there are differences between the two terms:

Adaptation refers to a process or action that changes a living thing so that it is better able to survive in a new environment. This could include actions such as building sea walls to protect people against flooding and sea level rise or planting trees to reduce air pollution and cool urban areas during periods of extreme heat.

Resilience describes the capacity or ability to anticipate and cope with shocks, and to recover from their impacts in a timely and efficient manner. This could include using agricultural practices that factor in climate risks such as planting drought, heat or flood tolerant species in at-risk regions or implementing crop variety and cover cropping to protect soil and decrease the likelihood of total crop failure following a climate-related shocks.

In general, communities engage in adaptation to become more resilient in the face of climate change and disasters. Because the determinants of adaptation and resilience are often the same, this page looks at the behavioural science around both concepts.

Examples of climate change risks and related resilience and adaptive measures

Environmental shocks, climate-related extreme weather events and continuous environmental degradation | Resilient and adaptive measures |

Tropical Storms (Cyclones, Hurricanes, Typhoons) and Tsunamis |

|

Flooding/Sea Level Rise |

|

Heatwaves |

|

Cold waves/Winter storms |

|

Droughts |

|

Landslides, Mudslides, Avalanches |

|

Earthquakes |

|

Who is at risk?

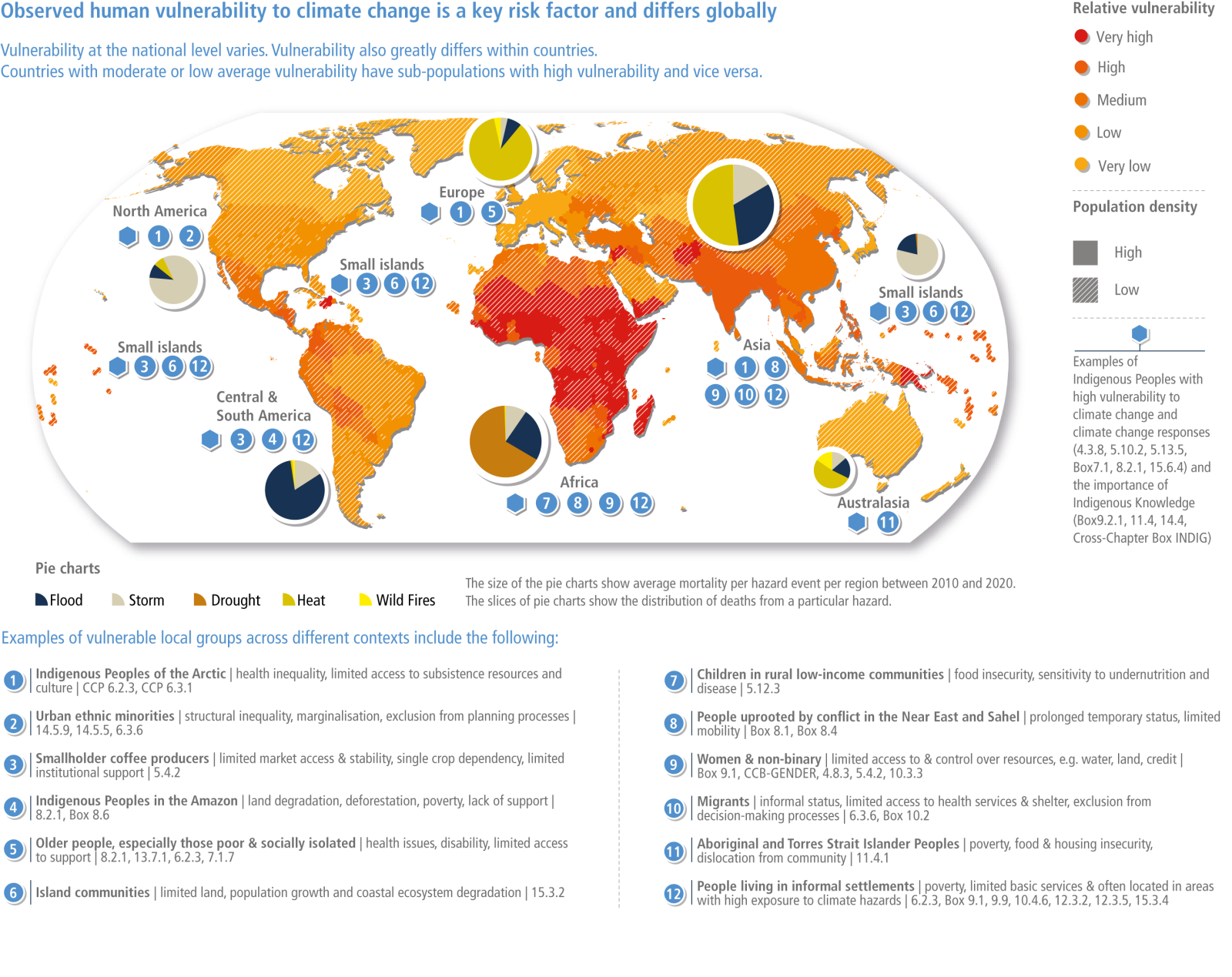

While everyone will feel the effects of climate change to some degree and different environmental hazards occur around the world, the poorest and most vulnerable will bear the brunt of the impacts both because of where they live (poorer communities and individuals tend to live in regions at greater risk from climate change and climate-related hazards), and because they have less financial security to insulate themselves against the negative effects. These communities in particular need support in adapting their lives and building resilience. UNICEF’s children’s climate risks index highlights varying levels of vulnerability across borders, demonstrating the greater climate risks faced by poorer countries. However, recent climactic events in Europe, Canada, Australia, and the US have demonstrated that richer countries are also vulnerable to climate change and need to invest in adaptation and resilience.

Minorities and marginalised groups also face higher risks from climate-related threats such as heatwaves, wildfires, tropical storms, sea level rise and flooding often due to pre-existing issues in comparison to other groups. In the UK, residents from ethnic minority backgrounds are four times more likely to live in areas vulnerable to heatwaves in comparison to the ethnic majority. Nearly half of all Indigenous peoples in Latin America have migrated to urban areas due to climate change, conflict and land use change which has threatened their way of life. Other markers of social status such as caste also influence an individual’s ability to adapt and build resilience in the face of climate change. Moreover, people with disabilities are often among the most vulnerable to climate change and disasters, often due to limited access to emergency support and limited consideration of their needs in adaptation plans.

Gender similarly influences an individual's vulnerability to climate change and ability to adapt. Pre-existing social dynamics make women and girls more vulnerable to the risks of climate change than men in many areas of the world and often less able to engage in adaptation than men. LGBTQ+ populations are also disproportionately affected by climate change and face greater risks and difficulties in adaptation and resilience building.

Climate change vulnerability therefore falls across several dimensions that must be considered when designing behavioural interventions:

Socio-economic |

|

Low-income communities | Economic constraints, limited access to healthcare, education, and emergency services; reliance on climate-sensitive occupations like agriculture and outdoor labour. |

Marginalised Groups (e.g., Ethnic, Racial, LGBTQ+, Indigenous) | Systemic discrimination, limited adaptation options, and legal barriers, often compounded by geographic risks (e.g., living in high-risk areas such as urban slums). |

People with Disabilities and Health-Compromised Individuals | Accessibility challenges in emergencies, limited mobility for evacuation, and disruption to essential medical treatments during climate events. |

Geographic |

|

Coastal and Low-Lying Areas | Sea-level rise, storm surges, increased flooding, and erosion; high vulnerability in Small Island Developing States (SIDS). |

Arid and Semi-Arid Regions | Drought, desertification, food and water insecurity, particularly affecting communities dependent on rain-fed agriculture. |

Urban Slums and Informal Settlements | Overcrowding, inadequate infrastructure, lack of basic services (clean water, sanitation, healthcare), amplified impacts of extreme events like floods and heatwaves |

Gender and Age |

|

Women and Girls | Societal roles (water collection, caregiving), limited decision-making power, increased exposure to risks like violence during displacement. |

Children and the Elderly | Physical vulnerability to health impacts (heatwaves, malnutrition), dependency on caregivers during emergencies, and higher mortality risks. |

Occupation-Specific |

|

Farmers and Agricultural Workers | Climate-sensitive livelihoods, changes in rainfall, temperature, and susceptibility to extreme weather events. |

Fishers and Coastal Workers | Ocean acidification, warming waters, shifts in marine ecosystems, and coastal degradation. |

Environmental Displacement and Migration |

|

Environmental Refugees and Migrants | Forced relocation due to uninhabitable conditions, integration challenges in new areas, including access to services, social support, and discrimination. |

Figure 8.6 Global map of vulnerability in Birkmann, J., E. Liwenga, R. Pandey, E. Boyd, R. Djalante, F. Gemenne, W. Leal Filho, P.F. Pinho, L. Stringer, and D. Wrathall, 2022: Poverty, Livelihoods and Sustainable Development. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1171–1274, doi:10.1017/9781009325844.010.

Psychological Determinants of Adaptive and Resilient Behaviours

While systemic factors such as financial resources, policy frameworks, and access to services are important, individual psychological determinants significantly influence how people perceive climate risks and their willingness to adopt adaptive and resilient behaviours. Understanding how awareness, risk perception, social norms, trust, and cultural beliefs shape decisions is essential for designing effective interventions. This section explores these psychological drivers and the common biases that impact behaviours around climate resilience and adaptation, providing guidance on how to tailor interventions to address these influences.

Awareness of Climate Change

Fundamentally, people need to be aware of climate change before thinking about its risks or the need to be resilient or adaptive to it. Awareness of the causes, consequences and risks surrounding climate change influence an individual's motivation to adapt and adopt resilient behaviours. If you have little to no knowledge of a threat, it follows that you are less likely to take measures to adapt to and protect yourself against the threat. Those with a good understanding of the mechanisms behind climate change and its consequences are more likely to adopt resilient behaviours and more likely to be willing to invest in adaptation. Thus, the availability heuristic plays a role in awareness of climate change. People tend to rely on examples that immediately come to mind when evaluating a situation, including decisions on climate adaptation and resilience. If an individual lives in a region that has not experienced significant negative effects of climate change in recent years and is not exposed to accurate media coverage on the climate crisis, vivid, immediate examples of climate change may not be immediately available to them when evaluating climate risks, making them less inclined to adopt resilient behaviours or adaptive measures. In contrast, those who have previously experienced negative impacts from climate change are more open to adaptation and resilience efforts as this past experience acts as a reminder of climate change’s impact and is “available” to them when evaluating their own risks. Though the influence of past experience on motivation to adopt resilient behaviours and adaptation has a shelf life, as humans have a tendency to forget too quickly the lessons of past disasters.

Additionally, because the potential consequences of the climate crisis are so alarming, some people have a tendency to “bury their head in the sand” and avoid all information relating to the climate crisis including information about their own risks, how to build resilience and how to adapt. This ostrich effect limits their awareness of climate change and exacerbates their risk as they are less likely to adopt resilient behaviours. Any programming on climate adaptation or resilience requires a component that engages with differing levels of public awareness around the continually increasing threat of an ever-degrading environment.

Risk Perception

There is often a disparity between an individual’s risk from climate change and disasters and their perception of that risk. Individuals often underestimate the probability of being exposed to disasters and climate change impacts and the potential severity of such impacts as a result of cognitive biases and heuristics that skew our perception of the risks and our ability and willingness to adapt to them. The impacts of climate change and disasters are so far outside of the perceived “norm” of everyday life that for many, building resilience and engaging in adaptation seems unnecessary. This normalcy bias, the tendency to underestimate the likelihood of an unusual, disruptive event and believe that things will function the way they typically have, reduces risk perceptions in relation to climate change and disasters, making people less resilient and less likely to invest in adaptation.

Even in scenarios where people accept the possibility of such a shock, most people have an ingrained optimism bias, in which they perceive their personal risk of being harmed by a negative event to be smaller than the risk of others. This bias can distort a person’s perceptions of their own risk from climate change and disasters, creating a belief that the negative effects either will not affect them or will not be as bad as predicted. This unwarranted optimism and its effect of on risk perception makes people less likely to engage in adaptation measures or adopt resilient behaviours as they consider them unnecessary.

Risk perceptions can also be distorted by cognitive myopia, a tendency to focus on overly short future time horizons when appraising costs and benefits, when it comes to thinking about climate change and disasters. The impact of climate change and climate-related disasters can be perceived to be too spatially and temporally far away for individuals to consider it a risk that needs to be addressed through resilience-building or adaptation. Most individuals tend to focus and respond to issues they consider to be immediately and personally relevant; given that climate change is occurring along a non-linear, longer timeline, measured in years, decades, and centuries, it is difficult for humans to grasp the full extent of the threat and why engaging in adaptation and adopting resilient behaviours now is necessary. Thus, the threat of sea level rise to a coastal community may be existential over a few decades but as the threat is not immediately obvious, an individual may downplay the risks and push off adaptation. By the time such a risk becomes urgent, it may be too late to start adapting.

Social norms, cohesion and trust

Social norms, informal rules that define acceptable and appropriate actions within a group, guide human behaviour including behaviour around climate change and disasters. A person’s perceptions of what is considered the status quo or norm in their community (descriptive norms) and what is approved of (injunctive norms) influences community behaviours around climate adaptation and resilience. If an individual believes that most other people in their community approve of and have adopted climate resilient behaviours and engaged in adaptation, they are more likely to do so as well. However, in communities where climate adaptation and resilient behaviours are not common, descriptive norms make people less likely to engage in resilient and adaptive behaviours as they perceive it be outside of the social norm.

Moreover, humans have a tendency to want to maintain the status quo when there is uncertainty about the potential benefits of an alternative such as adaptation. Likewise, in communities where climate adaptation and resilient behaviours are viewed negatively or sceptically, injunctive norms may make people less likely to adapt.

The effect of social norms, including norms around resilient and adaptive behaviours is stronger in communities with strong social cohesion and social capital as people will be more concerned with fitting in with their community. For example, strong social capital among elderly residents in the United Kingdom strengthened the misperception that they were not at risk from heat waves, creating a social norm of inaction and further increasing their vulnerability.

Furthermore, trust in authorities, service providers and between people within the same community can influence climate resilient and adaptive behaviours: If there is low social trust among a community in their government, climate scientists and experts, official warnings and advice about climate-related threats such as high temperatures, flooding, sea level rise and drought are more likely to be dismissed or ignored, leaving these communities more vulnerable to such risks as they fail to adapt their behaviours to build resilience. As was seen during climate-related extreme weather events such as Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Canadian wildfires in 2023 and European heatwaves in recent years, information provided by officials and experts such as early warning systems, evacuation orders and preparation advice was ignored by some groups due to low trust in these figures, resulting in higher fatalities and greater damage.

Cultural Beliefs

Cultural dimensions and values can also play an important role in adaptive and resilient behaviours. Individuals look at new problems, tasks and solutions through the lens of their preexisting values, and beliefs which influence their decision making. As to be expected, climate scepticism has been found to correlate with a reluctance to adapt to climate change. While some studies have found that spiritual and religious beliefs and organisations can play a positive role in encouraging climate resilient behaviours and adaptation, certain beliefs that either deny the existence of climate change or depict climate-change as divine intervention can also pose a barrier to adaptation, along with cultural differences, including differing conceptions of time and humans’ relationship to nature.

Studies have found that people from individualist societies are less likely to engage in collective action for adaptation than those from more collectivist societies due to a belief in individual freedom and self-reliance.

Self-efficacy and response efficacy

Self-efficacy and response efficacy are crucial psychological determinants influencing adaptive and resilient behaviours in the context of climate change. Self-efficacy refers to an individual's belief in their ability to perform actions that can lead to desired outcomes. In terms of climate adaptation, it reflects the confidence people have in their capacity to implement measures that protect themselves and their communities from climate-related risks. Response efficacy, on the other hand, pertains to the belief that the recommended actions will effectively mitigate or prevent the threats posed by climate change.

Individuals with high self-efficacy are more likely to engage in adaptive behaviours because they feel capable of making a difference. According to Bandura's Social Cognitive Theory, self-efficacy influences how people think, feel, and act. When individuals believe they can perform a task successfully, they are more motivated to undertake and persist in it. For example, a community that believes in its ability to organise and implement a flood defence system is more likely to take collective action to build such infrastructure.

Similarly, response efficacy affects whether individuals believe that the actions they take will have the desired impact. If people are confident that installing rainwater harvesting systems will effectively address water scarcity, they are more inclined to adopt such measures. Protection Motivation Theory suggests that both self-efficacy and response efficacy are necessary for protective action to occur; individuals must believe not only that they can perform the action but also that the action will be effective in mitigating the risk.

However, low self-efficacy can lead to feelings of helplessness or resignation, causing individuals to perceive climate change as an insurmountable problem beyond their control. This sense of powerlessness may result in inaction, as people doubt their ability to make meaningful contributions to adaptation efforts. Likewise, if response efficacy is low, individuals may question the effectiveness of adaptive measures, believing that such actions will not significantly reduce their vulnerability. For instance, a farmer might be hesitant to invest in drought-resistant crops if they are skeptical about the crops' ability to withstand prolonged dry periods.

Studies have shown that individuals with higher self-efficacy are more proactive in disaster preparedness and environmental conservation. Individuals who believed in their capacity to adapt were more likely to implement measures such as reinforcing their homes against extreme weather events. Similarly, when people have confidence in the effectiveness of an adaptive action (response efficacy), they are more likely to invest time and resources into it.

Cultural beliefs and past experiences also play a role in shaping self-efficacy and response efficacy. Communities that have successfully navigated previous environmental challenges may develop a stronger belief in their collective ability to cope with future risks. Conversely, communities that have experienced repeated failures in adaptation efforts might have diminished confidence in both their abilities and the effectiveness of proposed solutions.

Systemic determinants of resilient behaviours

It is important to note that beyond the psychological determinants, certain systemic factors are needed to be able to support behaviour change. For example, the upfront costs of adaptation can often act as a barrier to adaptation and resilience-building, especially for poorer individuals, communities and countries who often are forced to choose short-term affordability over actions that build their resilience over the longer term. Likewise, while someone may have strong motivation to adapt and build resilience, the resources that are needed may not be available: often poorer and marginalised communities, who express strong levels of willingness to adapt, do not have access to the resources they need to make any efforts effective. Relatedly, market forces can also act as a barrier or opportunity for adopting resilient and adaptive behaviours.

Finally, policies such as direct regulation, plans and capacity development, has been found to be a strong determinant of adaptive and resilient behaviours. Institutional policies that encourage and support adaptation and resilient behaviours and make the more resilient choice the default option result in an uptake in such behaviours. On the other hand, myopic policies that do not take climate change and disaster risks into account can discourage adaptive and resilient behaviours.

Designing Behavioural Science solutions for adaptive and resilient behaviours

Applying behavioural science principles to climate change resilience and adaptation efforts can significantly enhance the effectiveness of interventions. By understanding and addressing the psychological and systemic determinants of behaviour, we can design policies and programmes that encourage adaptive and resilient actions at both the policy level and the community and individual levels.

Community and Individual Level Interventions

Increase Awareness and Improve Risk Perception

Increasing awareness and understanding of climate risks and adaptive actions is foundational, and relatedly, ensuring that communities have accurate perceptions of the risk of the events is critical to motivating adaptative and resilient behaviours.

- Localised/Personalised Messaging: Tailoring messages to reflect local conditions and impacts makes climate risks more tangible and immediate, reducing psychological distance. Personalise the need for resilience and adaptation by emphasising the expected local, personalised impacts of climate change and climate-related disasters rather than broader effects. Using relevant, and recent examples of the negative effects of climate change, preferably within the local area and using localised messaging (mentioning local landmarks, using local messengers and stories) is more effective at increasing support for adaptation than warning about potential broader, future effects. Recent experience of extreme weather can create windows of opportunity for more resilient behavioural change. Align messaging on the need for adaptation and adoption of resilient behaviour with the beliefs, values and worldview of the target audience. This could include discussing climate change through the lens of their beliefs and emphasising how adaptation measures encourage behaviours they value such as protecting their traditional way of life and their communities.

- Decrease psychological distance: Improve risk perceptions and decrease the psychological distance of climate change by stretching time horizons in messaging on disasters and climate change: Instead of indicating that the likelihood of a severe hurricane next year is 1-in-100, experts could reframe their estimate as a greater than 1-in-4 chance that there will be at least one such hurricane in the next 25 years. This reframing may help overcome cognitive biases such as myopia to incentivise adaptation.

- Impact-Based Messaging: Focusing on how climate change will affect individuals' lives (health, livelihoods) increases personal relevance and urgency. Using impact-based messaging focusing on what climate change will do (endanger crops, homes, lives etc.) rather than what it will be (high temperatures, increasingly extreme weather events) is more effective in encouraging people to take action.

- Simplified Communication: Using clear, jargon-free language and visuals aids comprehension, especially among populations with varying literacy levels.

Enhance self-efficacy and response efficacy

Build confidence in people's abilities to take adaptive actions and belief in the effectiveness of those actions.

- Demonstrating Effectiveness: Showcasing successful examples for other similar communities of adaptation practices can enhance belief in the efficacy of those actions. Provide concrete advice on how to adapt and what constitutes resilient behaviours as well as real world examples of successful adaptation and resilience elsewhere to address low perceptions of self-efficacy. Warning communities about climate-related risks can be counterproductive without also providing concrete examples of effective adaptation measures they could take and of successful adaptation cases elsewhere. When people believe that adaptation can work, and most importantly can work for them, they are more likely to engage in adaptive behaviours.

- Highlight the co-benefits: Adaptive and resilient behaviours are often accompanied by economic, health, cultural or social co-benefits that can be more effective in convincing people to adapt than warning about the risks of climate change. For example, investing in retrofitting buildings with heat resilience measures lowers electricity costs by reducing the use of artificial cooling systems such as air conditioning. Moreover, highlighting how community-led adaptation can be an opportunity to build social cohesion and strengthen social bonds by working together towards a shared goal has been found to be effective in encouraging resilient and adaptive behaviours even among climate sceptics.

- Skill-Building Workshops: Providing training on adaptive practices (e.g., sustainable agriculture, disaster preparedness) increases people's confidence and capability.

Leverage Social Norms and Networks

Social norms strongly influence behaviour, and interventions can leverage this to promote adaptation.

- Social proof: Demonstrating how others have adopted resilience and adaptive behaviours increases compliance. For example, showing households how much water their neighbours consumes motivates them to reduce their own consumption. When faced with less common behaviours, highlighting that a behaviour is becoming more common, dynamic social norms, can motivate change, even if it's not yet the norm. E.g. Messaging that "more and more people are installing rainwater tanks" can encourage others to consider doing the same.

- Community Leaders as Champions: Engaging respected figures to model adaptive behaviours can shift norms and overcome scepticism. Working with community leaders including spiritual and faith leaders, on the need for climate change adaptation within their community and encouraging them to set an example can improve buy-in for adaptation measures. Even in communities where adaptation conflicts with a group identity, seeing others from within the community, especially community leaders adopt adaptive and resilient behaviours can encourage great uptake among the community. Working with experts who communities see as credible to disseminate important information on climate change, resilience and adaptation can foster greater trust in climate-related information and improve uptake of adaptation and resilient behaviours. Alternatively, even working with local celebrities can help get the message out in engaging ways.

Trust Building and Social Capital

Building trust within communities and between communities and practitioners enhances cooperation and collective action.

- Building Relationships: Consistent engagement and transparency build trust.

E.g. Corruption in local governments can massively limit the efficacy of disaster recovery and future interventions. - Participatory Approaches: Involving community members in planning and decision-making increases ownership and ensures interventions are culturally appropriate. E.g. Working with local communities to identify effective and appropriate strategies to prepare for and respond to extreme weather events.

Policy-Level interventions

Policy interventions are often necessary to facilitate behaviour change or increase its efficacy. Behavioural science can also help design and develop policy level interventions to further encourage adaptive and resilient behaviours.

- Default Options: Setting adaptive behaviours as the default choice increases uptake due to inertia and status quo bias. For example, automatically enrolling households in climate and disaster risk insurance programmes, with the option to opt-out, can lead to higher participation rates.

- Simplification and Convenience: Simplifying procedures and reducing barriers encourages action. Streamlining applications for adaptation grants or subsidies makes it easier for individuals and communities to access resources. Similarly, designing evacuation plans that are straightforward and easy to follow enhances their effectiveness during emergencies. Complex or confusing evacuation procedures can hinder timely responses, especially under the stress of imminent threats like floods or wildfires.

- Financial Incentives: Offering short-term financial incentives, such as tax credits, rebates, or grants for adopting adaptive technologies (e.g., installing solar panels, rainwater harvesting systems), motivates individuals to take action by reducing the upfront costs.

Indigenous solutions

While being mindful of the long and painful history of extractivism and repression imposed upon many indigenous peoples, including of indigenous knowledge, Indigenous solutions, climate resilient behaviours and adaptation practices in the face of a changing climate can play an important role among indigenous and non-indigenous communities alike. For example, Aboriginal Peoples in Australia practice cultural burning to manage the landscape and reduce the risk of wildfires. Similarly, agroforestry practices among indigenous peoples in West Africa, Central America, Papua New Guinea, the US and many other regions, reduces the risk of crop failure from soil erosion, diseases, drought and other extreme weather events. Furthermore, research conducted amongst local communities in Fiji found effective strategies to prepare for and respond to extreme weather events.